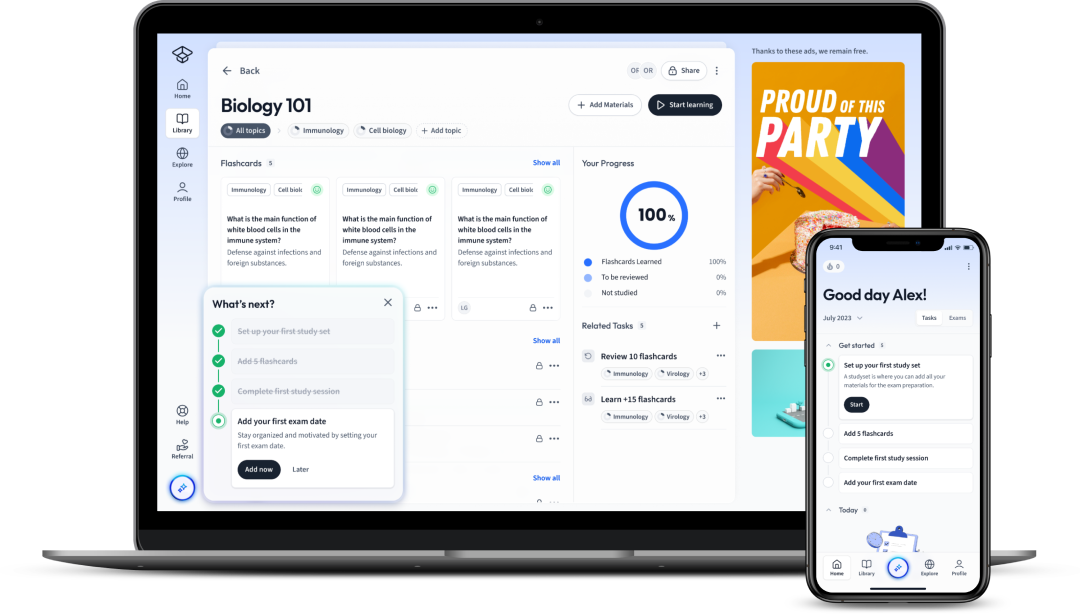

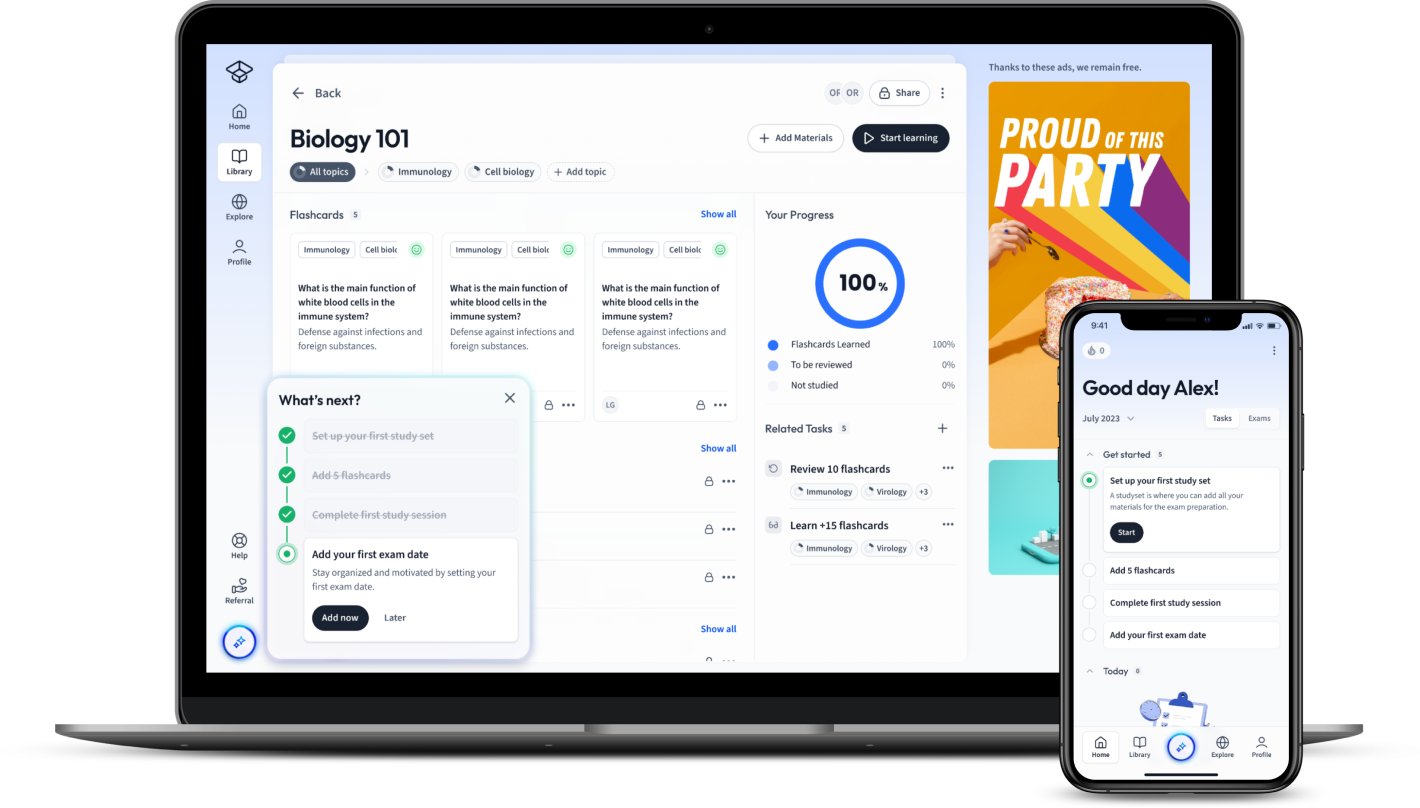

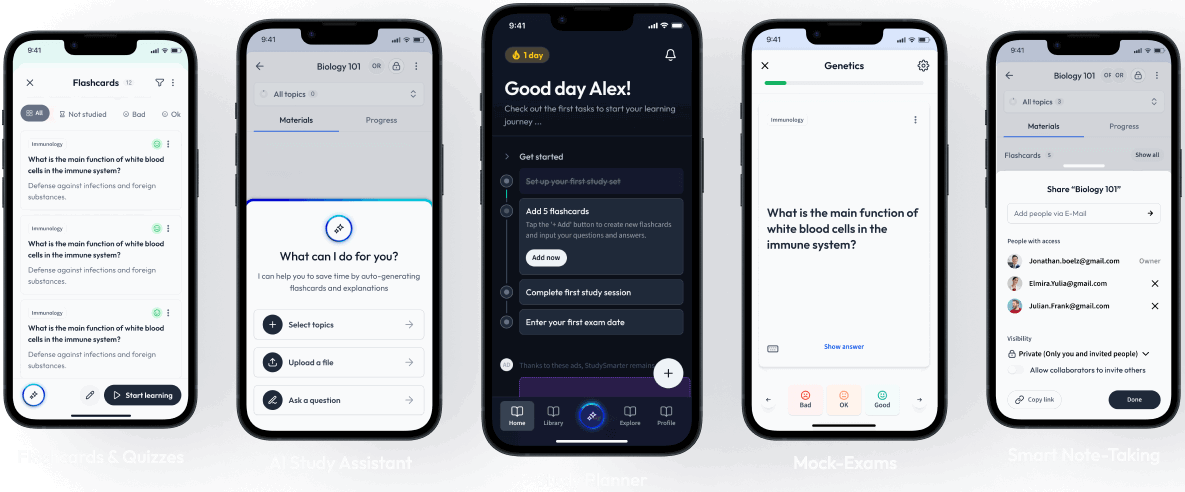

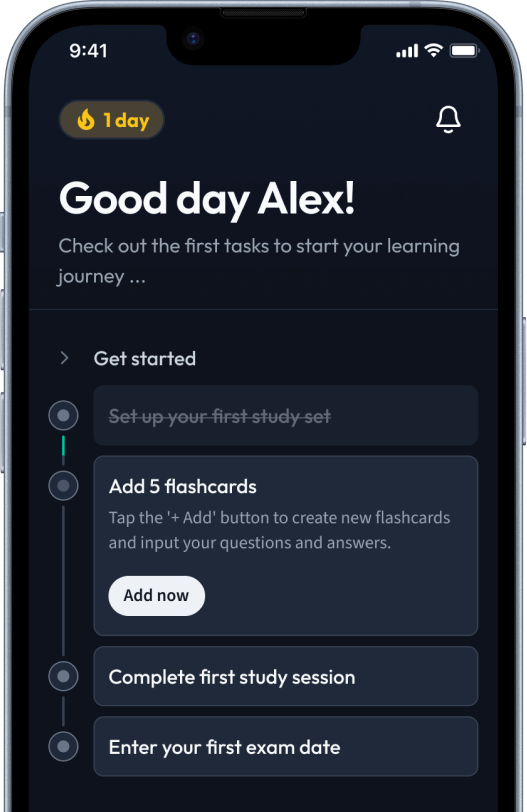

StudySmarter - The all-in-one study app.

4.8 • +11k Ratings

More than 3 Million Downloads

Free

Americas

Europe

Have you ever thought about how hard your body works day and night? Think about all the organs involved every time you breathe! When you breathe in, your lungs are filled with air, and from that air, oxygen travels to your bloodstream, and then carbon dioxide–a waste product–travels from your blood to your lungs and is expelled when you breathe out.

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenHave you ever thought about how hard your body works day and night? Think about all the organs involved every time you breathe! When you breathe in, your lungs are filled with air, and from that air, oxygen travels to your bloodstream, and then carbon dioxide–a waste product–travels from your blood to your lungs and is expelled when you breathe out.

And you might not have thought about it before, but your brain takes part in this process, too: it controls how fast or slow you breathe by sensing how much oxygen your body needs. Just imagine how many organs are involved in more complex tasks!

So, without further ado, let's talk about animal body systems!

As with any other living organism, an animal’s body is made up of building blocks called cells. Cells are so small that we typically cannot see them with our naked eye, so how do cells form something as complex as a living organism?

Cells are organized into successive layers, each with its own specific form and function (Fig. 1):

Cells that look similar and perform similar functions come together to form tissues.

Different types of tissues construct functional organs.

Organs that work together make up an organ system (or body system).

Different organ systems work together to perform specific functions to sustain the life of an organism.

With that, we can define the animal body system as follows:

An animal body system is a collection of organs that work together to perform specific life-sustaining functions in animals.

There are animals that lack organs or even well-defined tissues. Examples of these simple animals are sponges, corals, and placozoans.

You may have heard of sponges and corals before, as they are known inhabitants of the coral reef ecosystem.

On the other hand, you may be unfamiliar with placozoans–and you are not alone. Not much is known about them, even in the scientific community. These simple organisms are even simpler than sponges: whereas sponges are made up of 10 to 20 cell types, placozoans are made up of just four!

What are the different organ systems in animals? What are their main components and functions? As we move along, keep in mind that not all organ systems are the same; not all animals have all of these organ systems and some of them don’t have organs at all!

As we mentioned before, organ systems are composed of organs, which in turn are formed by different tissues. Importantly, organs have different types of specialised cells that coordinate to perform the organ's function.

Each organ system has its own organ composition, with tissues that can be specific to only that organ, or shared among different organs. To understand this better we will go into more detail about some specific organ systems.

Each animal organ system also has its own function. It's of vital importance for the animal's life that all organ systems perform their function well.

The digestive system is in charge of ingesting and breaking down nutrients so that they can be absorbed into the animal's system. The skeletal system is meant to provide support for the body and allow movement, working together with the skeletal muscle.

And these are just a few examples of the very specific and different functions of some animal body systems!

Each organ system has its own components and function, and we'll touch upon some of them to understand how they may vary.

The main parts of the digestive system are:

Fig. 2. Diagram of the human digestive system.

Fig. 2. Diagram of the human digestive system.

The digestive system breaks down food (digestion) and absorbs the smaller molecule it generates into the bloodstream as nutrients.

The process of digestion begins in the mouth, where food is mechanically broken down by chewing and mixed with saliva, which contains enzymes that begin the chemical breakdown of carbohydrates. The food then travels down the oesophagus and into the stomach, where it is further broken down by stomach acid and enzymes. From there, the partially digested food moves into the small intestine, where it is mixed with digestive juices from the pancreas and liver, and where the majority of nutrient absorption takes place.

The remaining waste products then move into the large intestine, where water is absorbed and the waste products are formed into faeces for elimination through the rectum and anus.

The skeletal system is made up of:

The most obvious function of the skeletal system is to provide structural support to the body. However, it has many other functions:

The muscular system is mainly made up of a specific cell type called muscle fibres. These are attached to bones, internal organs, and blood vessels. There are three types of muscle fibres, each with their specific functions and location within the body: skeletal, smooth and cardiac muscle fibres.

The muscular system gives the body the ability to move. Like the skeletal system, it also provides support to the body and contributes to regulating blood pressure by changing the diameter of the blood vessel lumen.

The integument system is made up of the skin and its derivatives, including hair, nails, and sweat glands. It is the body’s outermost protective layer. It also protects the body from injuries and infections and regulates heat within the body.

Animals that reproduce sexually have two reproductive systems: the male and the female reproductive system. Each species will have minor or major differences in their male and female reproductive systems, but they all share this basic characteristic: the male system produces sperm and the female system produces eggs.

The female human reproductive system is made up of:

The ovaries are not only the site for egg production, but are also a gland: they produce estrogen and progesterone, essential hormones for female holistic health. Apart from regulating egg maturation, estrogen and progesterone regulate bone density in females, as well as promoting cardiovascular health or a successful pregnancy.

The uterus generates the endometrium (which is released during the period) and is also the site for embryo implantation during pregnancy.

Fig. 5. Human female reproductive system.

Fig. 5. Human female reproductive system.

The male human reproductive system is made up of:

As with the ovaries, the testes are not only the site for sperm production but are also a gland that produces testosterone, which is also important for the holistic health of males. Testosterone is not only important for sperm production but also regulates muscle strength and bone density, among other functions.

The male reproductive system shares components and ducts with the excretory system, i.e. the urine and semen exit the male body through the same channel, the urethra. In the female reproductive system, though, urine and vaginal discharge exit the body through different channels (the urethra and the vagina, respectively).

Fig. 6. Human male reproductive system.

Fig. 6. Human male reproductive system.

The respiratory system is composed of:

The diaphragm and intercostal muscles are also essential for the respiratory system, as they expand and contract the lungs, which is where gas exchange takes place.

Fig. 7. Human respiratory system.

Fig. 7. Human respiratory system.

The respiratory system is responsible for gas exchange or the uptake of oxygen and the removal of carbon dioxide from the body.

The circulatory system is made up of:

Fig. 8. Diagram of the human circulatory system.

Fig. 8. Diagram of the human circulatory system.

The circulatory system is in charge of distributing materials such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, nutrients, hormones, and wastes within the body, as well as (in part) maintaining homeostasis in the body.

The immune and lymphatic systems are made up of:

Fig. 9. Diagram of the human lymphatic system.

Fig. 9. Diagram of the human lymphatic system.

The immune and lymphatic systems are responsible for fighting against infections, viruses, and even cancerous cell growth.

The endocrine system is a complex interconnected system composed of:

Hormones are chemicals that travel through the bloodstream to send messages to other parts of the body.

The endocrine system works with the nervous system to control the body’s internal organs and coordinate responses to stimuli from the external environment.

Fig. 10. The main organs of the human endocrine system.

Fig. 10. The main organs of the human endocrine system.

The nervous system is made up of:

The nervous system (along with the endocrine system) coordinates the body’s activities. It also detects stimuli from the environment and comes up with responses to them.

Stimuli (singular: stimulus) are things in the environment that elicit behavioural or physiological responses from organisms

Fig. 11. Diagram of the human nervous system (central and peripheral).

Fig. 11. Diagram of the human nervous system (central and peripheral).

The main components of the excretory system are:

It is responsible for disposing of organic wastes and regulating the volume of internal body fluids.

| Table 1. Animal organ systems and their components and functions | ||

|---|---|---|

| Animal organ system | Components | Function |

| Digestive system |

|

|

| Skeletal system |

|

|

| Muscular system |

|

|

| Integument system |

|

|

| Reproductive system |

|

|

| Respiratory system |

|

|

| Circulatory system |

|

|

| Immune and lymphatic systems |

|

|

| Endocrine system |

|

|

| Nervous system |

|

|

| Excretory system |

|

|

Organs that make up organ systems each have specific roles, so they are made up of specialized tissues and cells.

The stomach plays a major role in breaking down proteins. To carry out this function, the stomach uses a churning motion powered by stomach muscles and digestive fluids released by the stomach lining.

In turn, the production of digestive fluids requires specialized cell types: one that produces protein-digesting enzymes, another that produces hydrochloric acid, and yet another type that produces mucus to protect the stomach lining.

Some organs perform more than one role in the body and can thus belong to more than one organ system.

The pancreas not only produces enzymes that play a major role in the digestive system but also regulates the sugar level in the blood as part of the endocrine system.

The different organ systems work together to maintain homeostasis, the ability of a living system to maintain dynamic equilibrium while responding to changing external conditions. What we mean by dynamic equilibrium is that there is a fixed point that the body tries to maintain; when there are deviations from the set point, the body makes adjustments to get back to that point.

A cell tries to maintain a balance between having too little or too much water compared to its external environment. Likewise, the human body tries to maintain temperatures close to 37 °C (or 98.6 °F).

Think thermostat: you set a temperature that you’d like to keep. This is the fixed point.

When the room temperature is higher than the set temperature, the thermostat turns on the air conditioning system to lower the room temperature and bring it back to the fixed point. Likewise, when the room temperature is lower than the set temperature, the thermostat turns on the heater to raise the room temperature back to the fixed point.

Why do animals–and all living things for that matter–need to maintain homeostasis? This is because the body operates optimally within a set of internal and external conditions. Homeostasis is so important that the failure to maintain it can be harmful or even fatal to the organism.

So how does the body maintain homeostasis? When there is a change in the animal’s external environment, cellular receptors sense these changes and send signals to the control center (usually the brain), which in turn, generates a response that is sent to an effector, a muscle that contracts or relaxes or a gland that secretes.

The body uses negative and positive feedback mechanisms to maintain homeostasis.

A negative feedback loop is any homeostatic process that either increases or decreases the stimulus. If the level of the stimulus is too high, these processes lower it, and if a level is too low, these processes raise it. This is the primary mechanism used in homeostasis.

A positive feedback loop maintains or amplifies the direction of the stimulus, moving the level farther away from the set point. Unlike negative feedback, there are very few examples of positive feedback loops in animal bodies.

Various body systems may be involved in homeostasis, but all negative and positive feedback mechanisms that maintain homeostasis are controlled by the body's nervous and endocrine systems.

Let’s look at how different organ systems work together to maintain blood glucose levels in animals. When an animal eats, the following changes take place:

The digestive system breaks down food into glucose and other energy-rich molecules.

Cells in the intestine absorb glucose and release it into the bloodstream.

Blood glucose levels rise.

The nervous system senses this change and sends signals to specialized cells in the pancreas.

The pancreas produces and releases a hormone called insulin into the bloodstream.

Insulin lowers blood glucose levels.

On the other hand, when an animal has not eaten, its blood glucose levels will decrease, so the pancreas releases a different hormone–glucagon–to increase blood sugar levels. This process of glucose regulation is just one example of the body's various negative feedback loop mechanisms.

Now, let’s discuss an example of positive feedback. When a blood vessel is damaged, the following changes take place:

The damaged blood vessel initiates the clotting process.

Platelets in the blood start to stick to the damaged area.

These platelets release chemicals that recruit even more platelets.

As the platelets accumulate, more chemicals are produced, and more platelets are drawn to the location of the clot, forming a platelet plug.

Small molecules called clotting factors bring together components in the blood known as fibrin, sealing the inside of the wound.

In this case, we can see how the positive feedback loop speeds up the clotting process until the clot is big enough to stop the bleeding.

There are around 12 animal body systems: digestive, skeletal, muscular, integument, reproductive, respiratory, circulatory, immune, lymphatic, endocrine, nervous, and excretory systems. Note that organ systems may vary among different species of animals; some may not have all organ systems while others don't have organs at all.

Different organ systems work together to ensure life-sustaining processes, including those that maintain homeostasis. For example, the digestive system breaks down food into glucose and other energy-rich molecules, which are then absorbed by cells in the intestine and released into the bloodstream. This causes blood glucose levels to rise. The nervous system responds to this by signaling pancreatic cells to release insulin, which then brings down blood glucose levels.

No, not all animals have the same organ systems. Organ systems vary among different species of animals; some may not have all organ systems while other don't have organs at all.

Various body systems may be involved in homeostasis, but all negative and positive feedback mechanisms that maintain homeostasis are controlled by the nervous and endocrine systems.

The circulatory system is one of the organ systems whose major role is to transport substances such as oxygen, carbon dioxide, nutrients, hormones, and wastes in the animal body.

Flashcards in Animal Body Systems61

Start learningCells that look similar and perform similar functions come together to form ____.

Tissues

Different types of tissues construct functional _____.

Organs

Do all animals have the same organ systems? Explain.

No, not all animals have the same organ systems. Organ systems vary among different species of animals; some may not have all organ systems while other don't have organs at all.

Which animal body systems may be involved in homeostasis?

Various body systems may be involved in homeostasis, but all negative and positive feedback mechanisms that maintain homeostasis are controlled by the nervous and endocrine systems.

Which of the following animal body systems processes and absorbs food as nutrient molecules?

Digestive system

Which of the following animal body systems is made up of the skin and its derivatives, including hair, nails, and sweat glands?

Integument system

Already have an account? Log in

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in