StudySmarter - The all-in-one study app.

4.8 • +11k Ratings

More than 3 Million Downloads

Free

Americas

Europe

Did you know that over half of the nerve cells in the developing nervous system of vertebrates often perish shortly after they are created? Did you know that in a healthy adult human, billions of bone marrow and intestine cells die every hour?

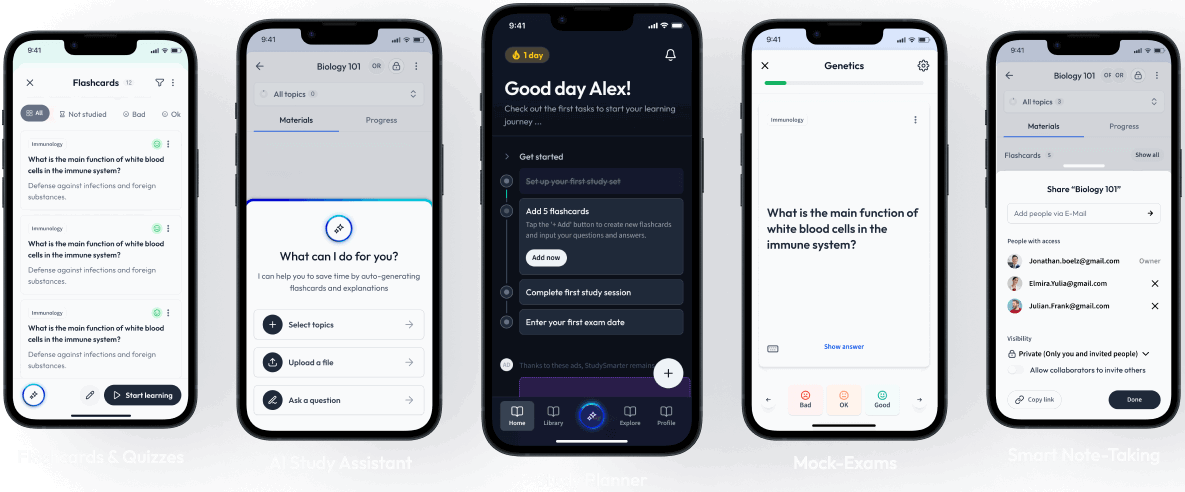

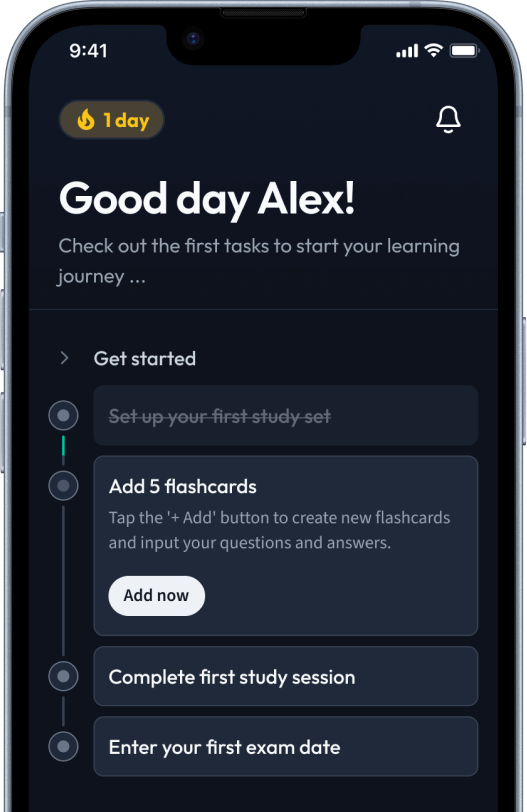

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenDid you know that over half of the nerve cells in the developing nervous system of vertebrates often perish shortly after they are created? Did you know that in a healthy adult human, billions of bone marrow and intestine cells die every hour?

Why do cells do something that seems so wasteful? In this article, we will discuss apoptosis or programmed cell death. We will start by discussing its definition, then we will go over details on how it works, what causes it, and what are some examples.

The number of cells in a multicellular organism is closely managed by regulating not only the rate of cell division but also cell death. Cells that are damaged, unnecessary, or potentially harmful can trigger apoptosis or "programmed cell death". The definition of apoptosis is shown below.

Apoptosis is basically a self-destruct mechanism that allows cells to die in a controlled way, preventing potentially harmful molecules from escaping the cell.

Cells that die due to injury usually swell, burst, and empty their contents onto their neighbors, a process known as cell necrosis. This can result in a potentially harmful inflammatory response.

In contrast, a cell that undergoes apoptosis shrinks and condenses without causing harm to nearby cells. Its cytoskeleton, nuclear envelope, and nuclear DNA break down, while its surface properties change, causing the cell to be phagocytosed before its contents leak out.

Phagocytosis refers to the process where a type of white blood cell called phagocyte envelopes and destroys a foreign substance or removes dead cells.

In addition to preventing the negative effects of cell necrosis, apoptosis also enables the cell that ingests the dead cell to recycle its organic components.

Figure 1 below visually compares the processes of necrosis and apoptosis.

Apoptosis is initiated by enzymes called caspases which cleave specific proteins in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Caspases can be found in all cells as inactive precursors (called procaspases) that are activated via cleavage by other caspases. Active caspases cleave and activate other procaspases, resulting in what is called a caspase cascade.

Some active caspases may also cleave other vital proteins in the cell. For instance, some caspases cleave the nuclear lamina, leading to its degradation; other caspases cleave proteins containing inactive DNAse allowing the DNAse to break apart DNA in the nucleus. In this fashion, the cell neatly and swiftly disassembles itself, and another cell immediately absorbs and digests the corpse.

Upon activation, apoptosis generally takes place in four stages:

The membrane of the mitochondria loses integrity. The cell shrinks and the chromatin condenses.

The plasma membrane starts to form bulges--a process called cellular blebbing.

DNA is broken down by enzymes called DNAse. Organelles including the nucleus collapse.

Apoptotic bodies enclose the components of the dying cell and are phagocytosed.

The chromatin--a complex of DNA and protein--is what makes up chromosomes.

The nuclear lamina is a fibrillar network of structural proteins lining the inner nuclear membrane of eukaryotic cells that is responsible for maintaining the shape of the nucleus and regulating gene expression by interacting with chromatin.

Apoptotic bodies are extracellular vesicles that are secreted by cells undergoing apoptosis. They contain substances from the dying cell, including its genetic information.

A cell has internal checkpoints that monitor its health; if irregularities are discovered, or when cells are damaged or stressed, a cell may start the process of apoptosis on its own.

The mitochondrial pathway is one of the best-understood pathways of procaspase activation that is initiated from within the cell. For cell damage to trigger apoptosis, a gene called p53 is required to start the transcription of genes that stimulate the release of cytochrome c--an electron carrier protein--from mitochondria.

Once cytochrome c is forced out of mitochondria and into the cytosol, it interacts and activates the adaptor protein Apaf-1. Most forms of apoptosis utilize this mitochondrial pathway of procaspase activation to start, speed up, or intensify the caspase cascade.

Apoptosis can also be initiated by external signals.

For example, normal animal cells usually have receptors that interact with the extracellular matrix. When cellular receptors bind to the extracellular matrix, a signal cascades within the cell. But when the cell moves away from the extracellular matrix, the signal is stopped, and apoptosis of the cell is initiated. This mechanism prevents cells from moving through the body and dividing uncontrollably.

The development of T-cells is another example of external signaling that results in apoptosis. Immune cells called T-cells are used by the immune system to target and destroy foreign macromolecules and particles by binding to them.

T-cells normally don't target self-proteins (those produced by their own bodies). If they do, it can result in autoimmune disease. For this reason, immature T-cells are screened to see whether they attach to so-called self-proteins so that they can develop the ability to distinguish between self and non-self. Should the T-cell receptor attach to self-proteins, the cell initiates apoptosis to kill any potentially harmful cells.

A biological pathway is a series of actions taken by molecules--whether activating or inactivating them--leading to a specific biological process. The mitochondrial pathway is one such pathway that involves the mitochondria.

The activation of the apoptosis pathway is literally a life-and-death situation. Because the caspase cascade is not only destructive but also self-amplifying, a cell cannot turn back once it has reached a key stage along the road to its demise. As such, it is important that mechanisms that regulate intracellular apoptosis are in place.

Procaspase activation is regulated in part by the intracellular proteins of the B-cell lymphoma 2 (Bcl-2) family, comprising over 20 members. Some members of this family, such as Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL, may contribute to the inhibition of apoptosis by preventing the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria.

Other Bcl-2 family members encourage procaspase activation and apoptosis rather than preventing them. For instance, some of these apoptosis promoters work by attaching to and deactivating the family members that prevent apoptosis from taking place, whereas others encourage the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria.

Another group of intracellular apoptosis regulators is the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family which are thought to prevent cell death in two ways: first, by binding to certain procaspases, they stop them from activating, and second, by binding to caspases, they stop them from being active. The efficacy of the death activation mechanism is considerably increased when mitochondria release cytochrome c to activate Apaf-1 together with a protein that inhibits IAPs.

Extracellular signals, which may either stimulate or suppress apoptosis, also control the intracellular cell death pathway. The main way that these signal molecules work is by controlling the quantity or activity of Bcl-2 and IAP family members.

Some instances of cell death are rather straightforward. For example, during the embryonic development of mice, cell death sculpts their paws by causing the individual fingers to break apart from what is initially a spade-like structure (Fig. 2).

Cell death also occurs when the tissue that they make up is no longer needed by the organism. For example, when a tadpole develops into a frog, the cells in its tail undergo apoptosis, causing the tail–which is not needed by the frog–to disappear.

Cell death also balances with cell growth in adult tissues. Without such balance, the tissue would expand or contract. For instance, if a portion of an adult rat’s liver is removed, liver cell growth increases to compensate for the loss.

On the other hand, a rat treated with the drug phenobarbital–which stimulates cell growth in the liver, resulting in the enlargement of the liver–and then the treatment is stopped, programmed cell death increases until the liver has shrunk back to its original size. This demonstrates how the regulation of both cell death and cell growth rate keeps the liver at a constant size.

When apoptosis does not function properly, cells with potentially dangerous mutations may not be eliminated. Instead, such cells can grow uncontrollably, leading to the formation of a tumor. This happens because some sensors in cancer cells may fail to recognize signals that trigger apoptosis. One such sensor is p53 (which we discussed earlier in the mitochondrial pathway). A functioning p53 typically prevents the formation of cancer through apoptosis. In about half of all cancers, there are mutations found in the p53 gene.

Apoptosis is basically a self-destruct mechanism that allows cells to die in a controlled way, preventing potentially harmful molecules from escaping the cell.

Alongside cell division, apoptosis or programmed cell death is a mechanism for managing the number of cells in an organism. It also prevents the inflammatory response that could result from necrosis (uncontrolled cell death). It also enables the cell that ingests the dead cell to recycle its organic components.

Upon activation, apoptosis generally takes place in four stages:

Apoptosis occurs when there are cells that are damaged, unnecessary, or potentially harmful.

Cancer cells fail to recognize signals that trigger apoptosis.

Flashcards in Apoptosis15

Start learningThis process can be described as a self-destruct mechanism that allows cells to die in a controlled way, preventing potentially harmful molecules from escaping the cell.

Apoptosis

During this process, cells that die swell, burst, and empty their contents onto their neighbors.

Necrosis

During this process, a type of white blood cell envelopes and destroys a foreign substance or removes dead cells. This process plays a role in preventing the contents of dying cells from being released.

Phagocytosis

What enzyme initiates apoptosis by cleaving specific proteins in the nucleus and cytoplasm?

Caspase

Explain the process of caspase cascade.

Caspases are enzymes that cleave specific proteins in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Caspases can be found in all cells as inactive precursors that are activated via cleavage by other caspases. Active caspases cleave and activate other procaspases, resulting in what is called a caspase cascade.

Explain how the mitochondrial process works.

For cell damage to trigger apoptosis, a gene called p53 is required to start the transcription of genes that stimulate the release of cytochrome c--an electron carrier protein--from mitochondria. Once cytochrome c is forced out of mitochondria and into the cytosol, it interacts and activates the adaptor protein Apaf-1. Most forms of apoptosis utilize this mitochondrial pathway of procaspase activation to start, speed up, or intensify the caspase cascade.

Already have an account? Log in

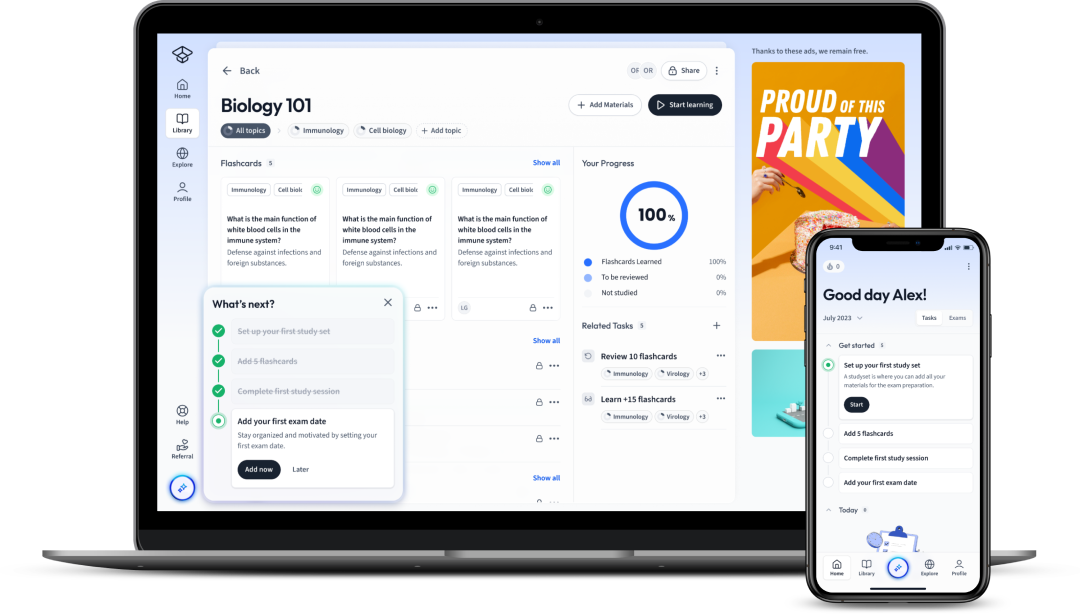

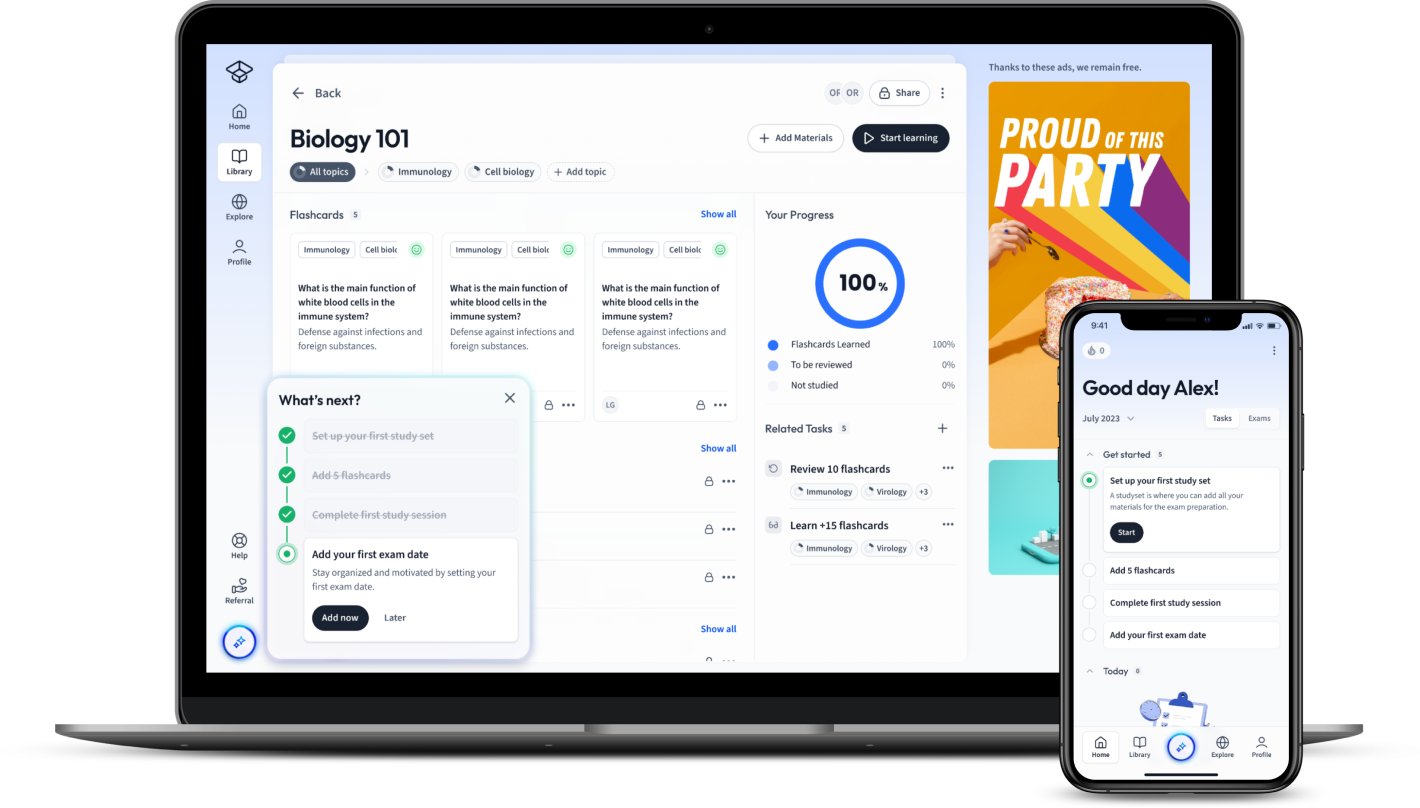

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in