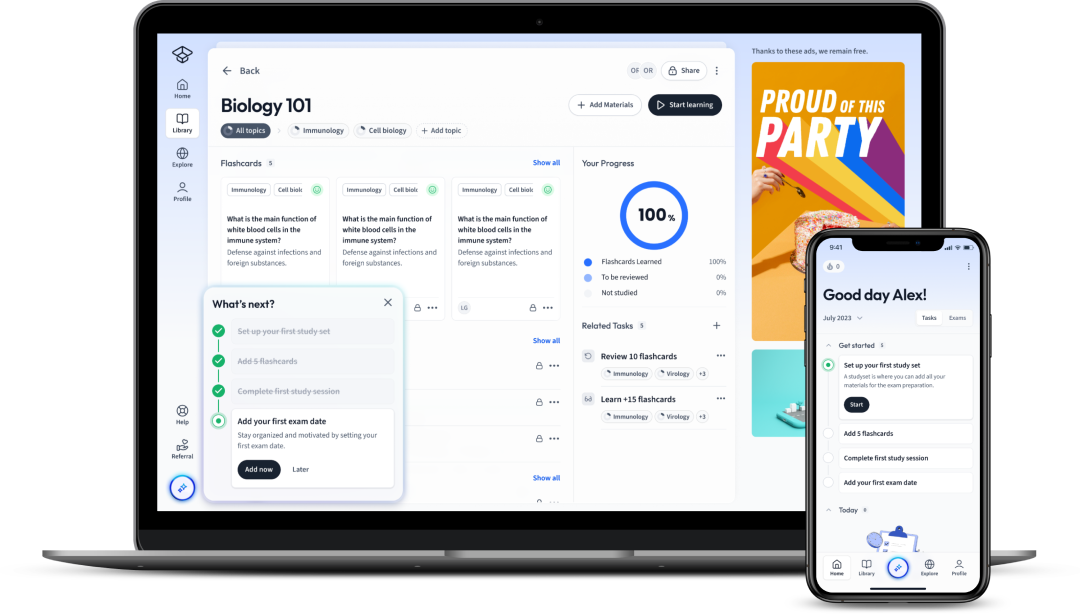

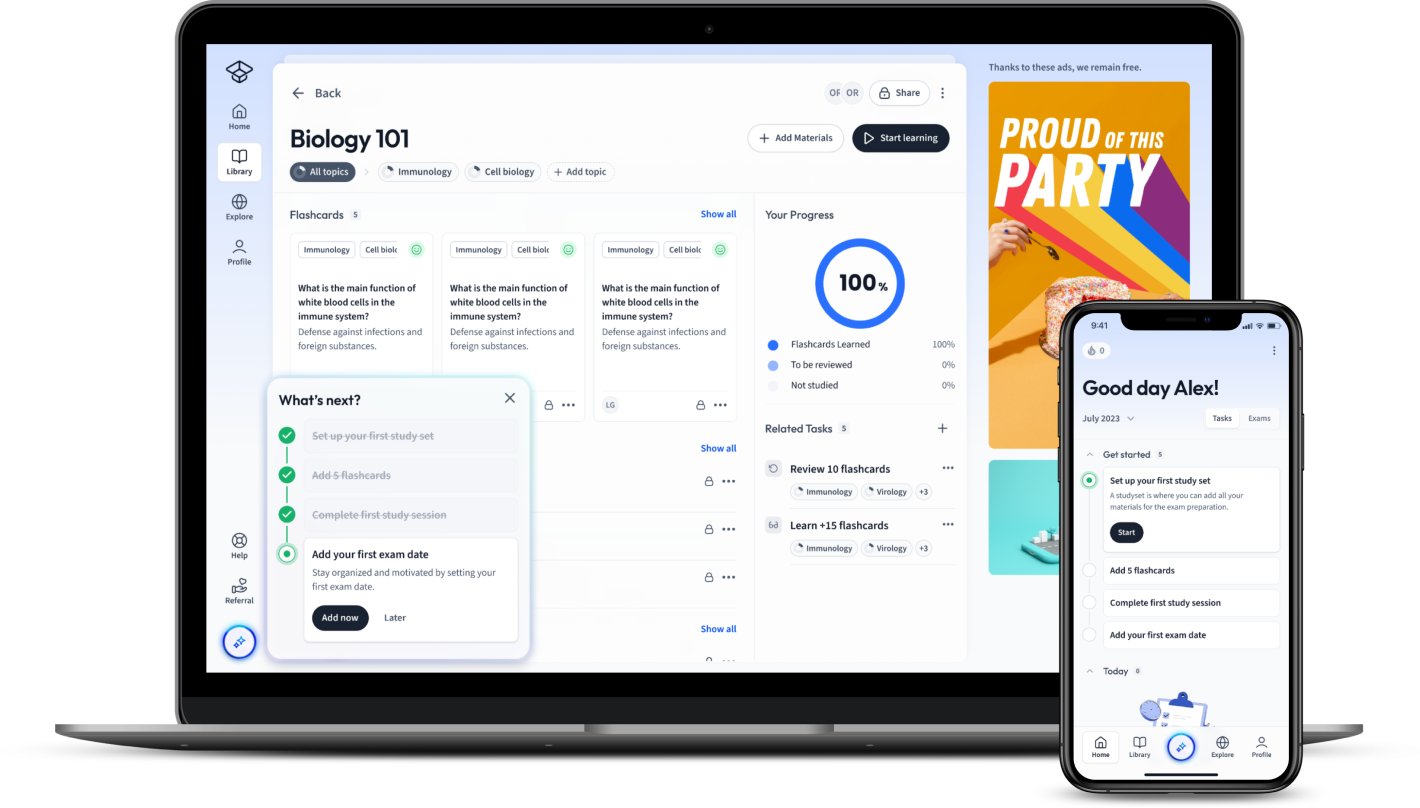

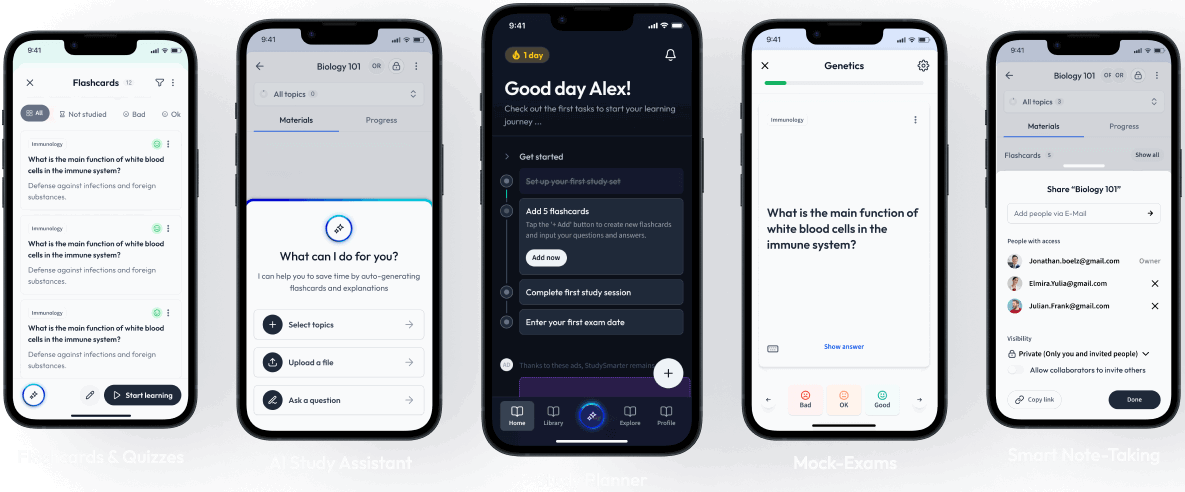

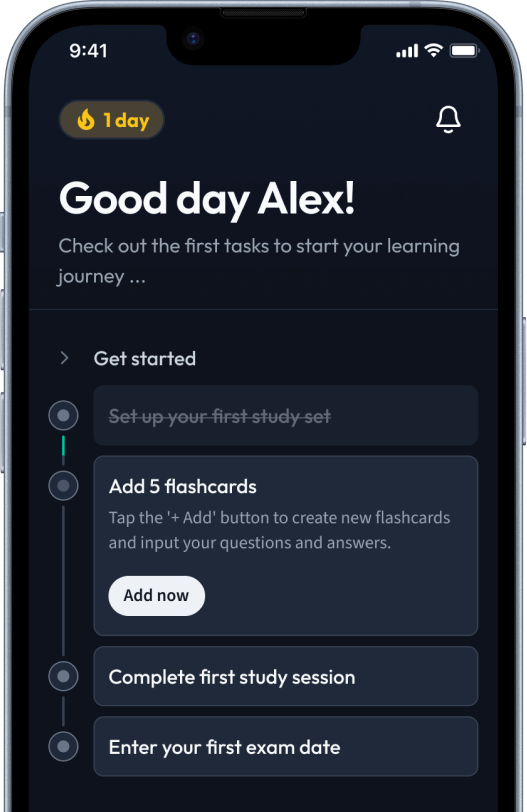

StudySmarter - The all-in-one study app.

4.8 • +11k Ratings

More than 3 Million Downloads

Free

Americas

Europe

When looking at a plant or animal cell under a microscope, it is usually easy to spot the nucleus as it is the more conspicuous structure inside the cell. The nucleus was the first cell organelle to be discovered. The nucleus in a eukaryotic cell encloses the DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid). The DNA contains the specifications for the cell function; therefore, the nucleus controls all the cellular activity.

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenWhen looking at a plant or animal cell under a microscope, it is usually easy to spot the nucleus as it is the more conspicuous structure inside the cell. The nucleus was the first cell organelle to be discovered. The nucleus in a eukaryotic cell encloses the DNA (Deoxyribonucleic acid). The DNA contains the specifications for the cell function; therefore, the nucleus controls all the cellular activity.

The cell nucleus is distinctive of eukaryotic cells; eukaryote means "true nucleus", contrasting with prokaryotic cells (in bacteria and archaea) that do not have a nucleus. In prokaryotic cells, the genetic material is concentrated in a region of the cytoplasm called the nucleoid. Under a microscope, it is easy to differentiate eukaryotic from prokaryotic cells because of the nucleus (and the presence of other organelles as described in our Eukaryotic Cells article).

The nucleus (plural, nuclei) has a spherical or elliptical shape and is delimited by two membranes (see figures 1 and 2). Each of these membranes is a phospholipid bilayer, like the one that composes the plasma membrane (the plasma membrane has one bilayer, the nucleus has two bilayers)

The structure formed by the inner (facing the inside of the nucleus) and outer (facing the cytoplasm) bilayered membranes is called the nuclear envelope. The outer membrane is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum in the cytoplasm, and both organelles work together as part of the endomembrane system of the cell.

The nucleus is the membrane-bounded organelle containing genetic material (chromosomes) in a eukaryotic cell and controls cellular activity.

There are nuclear pores all over the nuclear envelope through which ions and molecules move between the nucleus' interior and the cytoplasm. Proteins surround each nuclear pore forming a pore complex that controls the passage of proteins, RNA molecules, and larger components.

The inner part of the nuclear envelope is covered by the nuclear lamina (except where the pores are), a mesh-like structure composed of protein filaments. The lamina gives support to the nuclear envelope and maintains the nucleus shape.

The functions of the nuclear envelope and its lamina are not well understood; however, they seem to be involved in fundamental processes for the cell. At least eight human diseases result from mutations in the gene LMNA, which carries the information for a type of nuclear lamins. These diseases present similarities with defects related to aging, like reduction in functions such as cellular proliferation and the ability to repair tissue. One of these is progeria, an inherited syndrome that produces symptoms of premature aging (including loss of subcutaneous fat, reduced muscle development and bone density, and alopecia). The average age range of death for progeria patients is 12-15 years.

We find most of the cell’s genetic material and one or more nucleoli (singular nucleolus) inside the nucleus. The nucleolus looks like a dense mass of granules and fibers, not delimited by a membrane. This mass is composed of regions of chromatin involved in ribosome synthesis, associated with RNA molecules and proteins. The nuclear components are immersed in a semi-solid fluid that fills the inside of the nucleus, called the nucleoplasm.

The DNA in eukaryotic cells (plant, animal, fungi, and protist cells) is organized in multiple linear chromosomes. DNA is an extremely large and thin molecule that could easily get tangled and break. Thus, it is associated with proteins that help maintain its structure. The complex of DNA and proteins is called chromatin and makes up the chromosomes. In a cell that is not dividing or reproducing, the chromosomes are somewhat loose and look like a granular agglomerate of threads. It is only during the division process that the chromatin condenses (it coils up and thickens) and becomes visible (figure 2, B-D, shows the nuclei of plant cells that are dividing).

You can check more about chromosomes here and cell division here.

We say that the nucleus contains most of the cell’s genetic material (nuclear DNA) because mitochondria and chloroplasts have some genes of their own (both these organelles most probably derived from ancestral free-living bacteria that were engulfed by an ancestral host cell through endosymbiosis, and therefore had their own genetic material initially).

The cell nucleus has two main functions:

Figure 2. Section of an onion root tip. Stained cell nuclei are visible in different cell cycle stages. A) interphase, B) early stage of cell division, C and D) cells undergoing mitosis. Source: modified from Berkshire Community College Bioscience Image Library, public domain, flickr.com.

The nucleus is the cell's control center because it encloses the genetic material, which contains the information that specifies all the cell activity. A chromosome comprises hundreds to thousands of smaller segments containing the genetic information for specific traits (for example, the color of an animal’s fur). Each of these segments is a gene. The sequence of nucleotides in a gene works as a code (called the genetic code) for making a protein.

Genes do not synthesize proteins directly. The process to go from gene to protein is called gene expression (because proteins are the corresponding expression of genes) and involves two steps, transcription and translation. The nucleus is the site where transcription occurs. The nucleus transcribes (or copies) the nucleotide sequence from a gene to the corresponding RNA sequence, which is called messenger RNA -mRNA- (remember from nucleic acids structure that RNA is similar to a DNA molecule, except that in RNA, the sugar part is ribose instead of deoxyribose and has a uracil base instead of thymine).

In other words, the DNA sequence serves as a template that is transcribed into mRNA. This segment of mRNA then leaves the nucleus through the nuclear pores and will be translated into the corresponding protein by ribosomes in the cytoplasm.

This is a simplified description of transcription; we study the complete process of gene expression in more detail in the Regulation of Gene Expression and Transcriptional Regulation articles.

The nucleolus also transcribes segments of the DNA that encode ribosomal RNA -rRNA-. As the name indicates, the rRNA is involved in the production of another cell organelle, the ribosome. Proteins from the cytoplasm enter the nucleus through the nuclear pores and, in the nucleolus, are assembled with the rRNA molecules into ribosome subunits. Ribosomes are composed of one large and one small subunit. The ribosome subunits leave the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where the ribosome assembly is completed.

All the enzymes and other proteins needed inside the nucleus (like the proteins associated with the DNA or the ones required to make the ribosome subunits) are synthesized in the cytoplasm by ribosomes and then enter the nucleus through the nuclear pores. On the other hand, RNA molecules and ribosome subunits synthesized in the nucleus must leave through the pores to participate in protein synthesis in the cytoplasm.

All eukaryotic cells have a nucleus, including animal, plant, fungi, and protists cells. There are no major differences in the structure or functions of the nucleus among eukaryote organisms. Some eukaryotic cells can lose their nucleus as part of their development (like red blood cells in mammals), or sometimes errors occur during cell division, and one of the daughter cells can keep both nuclei while the other has no nucleus (is anucleated).

Mature red blood cells in mammals do not have a nucleus. Red blood cells (RBCs), like all eukaryotic cells, do have a nucleus when formed. However, their function is to transport oxygen to every cell in our body. The more hemoglobin (the molecule that binds to oxygen) an RBC can carry, the more efficient it will be. Hence, RBCs eject their nucleus and other organelles when they mature to have more space for hemoglobin molecules.

What does it mean for a cell not to have a nucleus? As expected, the nucleus’ functions are not performed in mature RBCs. They do not transcribe DNA to RNA nor synthesize proteins (in consequence, they do not have most organelles to do this either). RBCs cannot divide either and thus are produced in the bone marrow; they have a lifespan of 100-120 days and are continuously being replaced. RBCs in other vertebrates (fish, reptiles, birds) are bigger than in mammals, and they do have a nucleus, but it is inactive.

Leslie Mounkes and Colin Stewart, Aging and nuclear organization: lamins and progeria, Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2004

Cristin Carr, How red blood cells nuke their nuclei, February 10, 2008. Whitehead Institute.

https://wi.mit.edu/news/how-red-blood-cells-nuke-their-nuclei

No, prokaryotic cells do not have a “real” nucleus delimited by a membrane. They do have a nuclear region where the genetic material is concentrated.

Yes, plant cells are eukaryotic cells and have a nucleus.

No, not all cells have a nucleus. Prokaryotic cells do not have a nucleus, while eukaryotic ones do. However, some eukaryotic cells can lose their nucleus as part of their development, like mature mammalian red blood cells (erythrocytes).

Yes, eukaryotic cells have a nucleus. Some eukaryotic cells can lose their nucleus as part of their development, like mature mammalian red blood cells (erythrocytes), but they originally had a nucleus.

The cell nucleus encloses the genetic material and has two main functions: duplication of the genetic material (chromosomes) to be distributed during cell division; and transcription of protein synthesis’ specifications from DNA to RNA.

Flashcards in Cell Nucleus14

Start learningWhich of the nucleus components is continuous with the endoplasmic reticulum?

outer membrane of the nuclear envelope

We can find two bilayered membranes surrounding the:

nucleus

The structure responsible for ribosome assembly is the:

nucleolus

We can find a single bilayered membrane surrounding the:

cell

Which one of the following sentences is true?

Enzymes and other proteins move from the cytoplasm to the nucleus

Which structure controls the passage of molecules and larger components between the cytoplasm and the nucleus?

pore complexes

Already have an account? Log in

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in