StudySmarter - The all-in-one study app.

4.8 • +11k Ratings

More than 3 Million Downloads

Free

Americas

Europe

Studies suggest that viruses have been on earth since the dawn of time yet, according to the criteria of life, viruses are not considered living. Viruses are responsible for the majority of diseases that plague the earth and constantly evolve by developing new ways to evade our immune defenses. So what are viruses exactly? Are they simply strands of genetic material that try to take over our bodies? Or are they something more complex? Let's dive deeper into the history and evolution of viruses to find out.

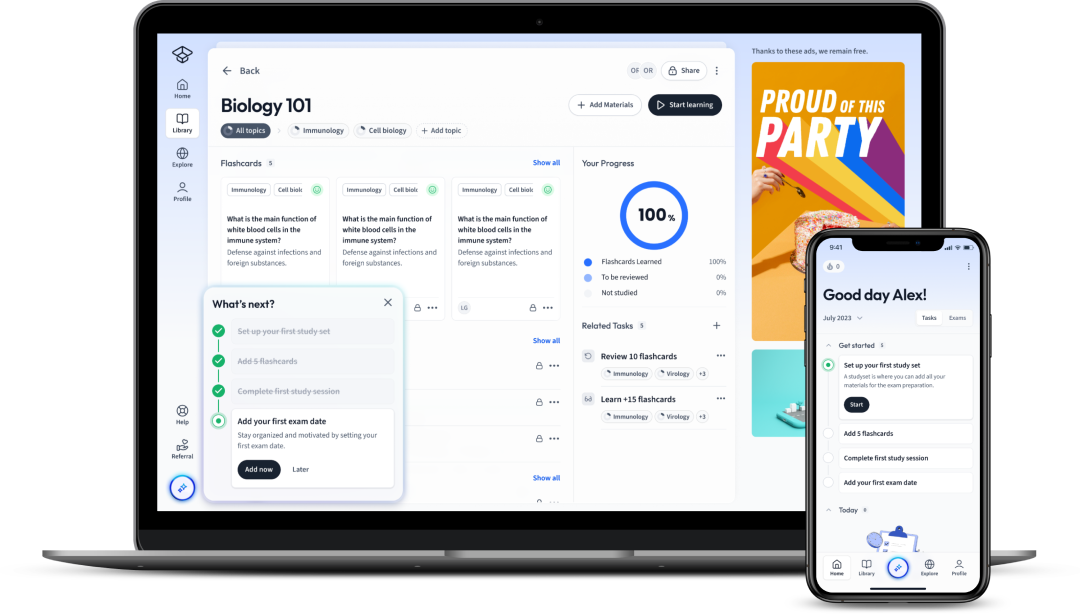

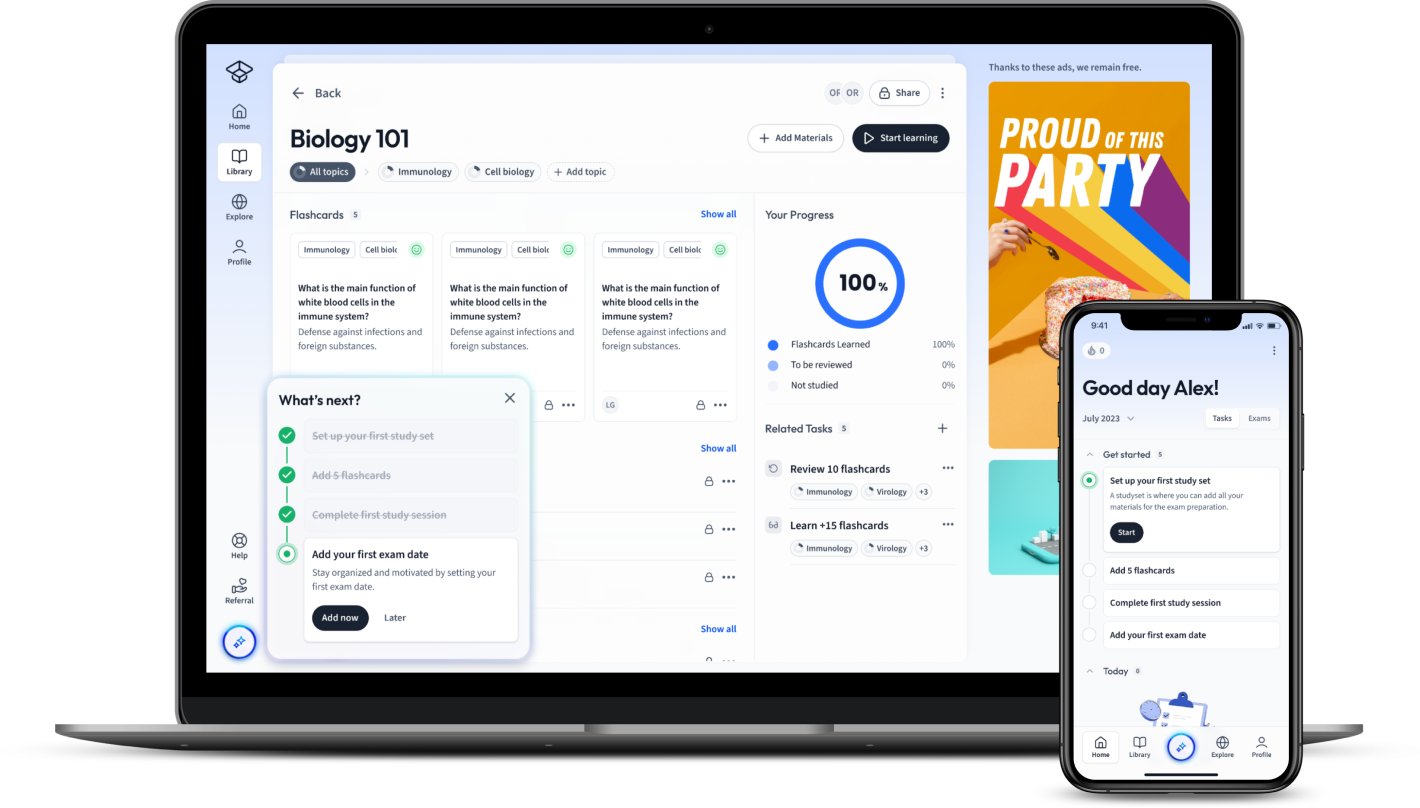

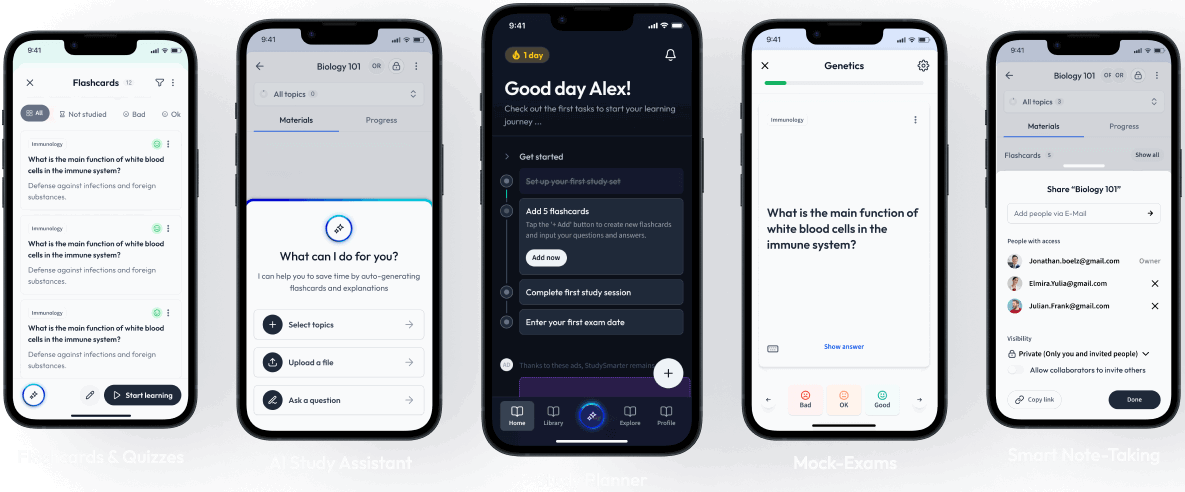

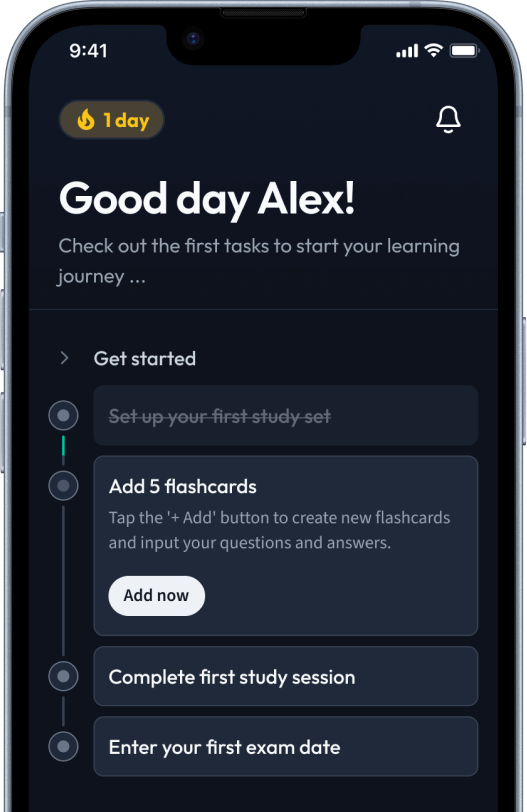

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenStudies suggest that viruses have been on earth since the dawn of time yet, according to the criteria of life, viruses are not considered living. Viruses are responsible for the majority of diseases that plague the earth and constantly evolve by developing new ways to evade our immune defenses. So what are viruses exactly? Are they simply strands of genetic material that try to take over our bodies? Or are they something more complex? Let's dive deeper into the history and evolution of viruses to find out.

The exact way that viruses evolved over time still remains a mystery to this day; however, researchers have some theories. Over the course of modern science, three hypotheses explaining viral origin have emerged:

viruses are relics of a pre-cellular life form;

viruses were produced by the devolution of a unicellular organism;

viruses originated from fragments of genetic material that escaped from the control of the cell and became parasitic.

As the first viruses emerged, they infected their hosts which were most likely bacteria since they are the earliest life form. According to theory 3, viruses mutated into a more parasitic entity and relied more on a host species to survive. As viruses infect different hosts, the viral genomes mutate into different viral strains and this is how viruses evolve over time.

The regressive theory of viruses hypothesizes that viruses originated from a more complex free-living ancestor that "de-evolved" by losing genetic information over time.1 As the virus precursor/ancestor lost genetic material, the hypothesis suggests that it developed a parasitic way of surviving.

Viruses are technically not living, because they do not contain enough genetic material to form a complete cell.

Since viruses are not alive, they cannot be classified as parasites. Instead, the way that viruses replicate can be labeled as "parasitic". This is because viruses need to live inside humans to reproduce themselves.

Virus: An acellular, parasitic genetic material that is not classified within any kingdom. Parasite: An organism that lives within another organism of a different species (host) and survives by stealing nutrients from the host.

Viruses are not all identical and come in many different shapes and sizes. The viruses that exist today can be categorized into groups based on the way they store their genetic material. Classifying viruses based on their genome is known as the Baltimore classification method.

Examples of negative-sense RNA viruses include Influenza and Ebola.

We will be discussing these viruses later on in this article.

Unlike influenza and Ebola, positive-sense RNA viruses are comprised of the positive mRNA strand and are able to be translated into proteins readily within the host.2

Retrovirus: A virus that stores its genetic material as RNA.

Data to support the regressive theory exists, but it is hard for researchers to know the exact way that viruses evolved without witnessing them firsthand. Analysis of multiple viral genomes provides an interesting insight into how viruses function and may have regressively evolved. Genomic analysis of a large group of DNA viruses called the NCLDV'S best highlights the regressive hypothesis.

NCLDV'S include viruses such as smallpox.1 These types of viruses are quite large and rely less on their host for replication and survival.1

For instance, smallpox is able to produce functional mRNA's within the host cell cytoplasm without the need for a complete take over the host cell's transcription machinery.1

In contrast, smaller viruses such as influenza, possess much smaller genomes and rely entirely on the host cell's transcription machinery for replication.1 Analysis of these two viruses suggests that viruses are regressive. The influenza virus could have evolved from an organism that was more dependent upon its host which could explain why the influenza virus has less genetic material.

Now that we have a general idea of where viruses come from, let's discuss their role in human evolution. Are viruses simply here to take over our bodies? Or did they help us evolve into the complex organisms that we are today?

The answer may surprise you!

Emerging research suggests that 30% of human protein adaptation since humans evolved from chimpanzees has been driven by viruses.1 This means that viruses have been partially responsible for diversifying us from our primate ancestors. This data makes sense because when a host population is faced with a pandemic, the population must genetically adapt in order to fight and withstand the infection.

If the population does not adapt, the virus will overtake each organism in the population until that population goes extinct. If you take a closer look at the human genome, you will see that a large portion of our genetic code matches the genetic code of common viruses. This is because as we are infected with a virus, our bodies store some viral genetic code within our genomes so that we are better equipped to fight that virus if it infects us again. So, viruses may be the reason why our life expectancy has generally increased over the years, but research suggests that the infiltration of viruses within human genomes may not be 100% beneficial. See figure 1 for a visual of common viruses.

Currently, the human genome consists of around 22,000 genes and roughly 8% of our DNA consists of remnants of ancient viruses and is theorized to contribute to modern-day diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), cancer, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).3 A geneticist named Barbara McClintock discovered that certain portions of our DNA are able to move around our genomes by copying and pasting themselves.3

She later names these genes "jumping genes".3 Since Barbara's discovery, later scientists determined that these jumping genes originated within the viral portion of our genome. It is possible that these jumping genes could cause frameshift mutations within our genome leading to the evolution of human diseases such as MS; however, more research is needed on this subject to know for sure.

Genomic studies suggest that influenza viruses have existed for millions of years.4 Currently, the main reservoir for influenza are birds; however, influenza viruses frequently infect other species including humans.4 Molecular sequencing of influenza A from birds and mammals suggests that it is a highly evolving virus with a high mutation rate.4 Despite the genetic variations within the host species influenza A infects and the subtypes of influenza A viruses that exist, research reveals that the genetic diversity of current influenza A viruses originated fairly recently. Studies suggest that the current influenza A viruses originated sometime in the 19th century. Scientists hypothesize that there was a large-scale "selective sweep" of the influenza genomes sometime during the 1800s causing all avian and mammalian influenza A viral lineages to originate from the time of the sweep.4 After the sweep, the influenza A viruses continued to evolve at a fast rate.

As previously mentioned, influenza A viruses infect hosts in multiple species. Usually, many cross-species transmission infections of influenza usually result in small spillover infections, there have been many times where a spillover infection grew into a full-blown epidemic. This was seen during the early 2000s when swine flu (H1N1) spread like wildfire throughout the US and other countries.

Due to its ability to jump between host species and its fast mutation rates, influenza A viruses evolve at a rapid rate. The three mechanisms by which influenza viruses evolve are: mutation (antigenic drift), re-assortment (antigenic shift), and recombination.4

The influenza A viruses undergo significant point mutations which causes the virus to gradually evolve. As the virus infects the host, the host's immune system learns how to fight the virus which is why viruses need to mutate in order to develop ways to evade the host's immune system attacks.

Point Mutation: A genetic alteration caused by the substitution of a single nucleotide for another nucleotide. EX. GAG turning into GUG. This is a point mutation that causes sickle cell anemia

The Hemagglutinin HA protein is responsible for binding influenza a virus to host cells. The neuraminidase (NA) protein is responsible for cleaving the host cell receptor to initiate viral entry into the host cell.

Another way that influenza viruses evolve is through re-assortment. Re-assortment allows different influenza strains to exchange RNA segments with one another which results in the production of a new strain of the virus. Re-assortment is likely how the swine flu was able to affect humans. One strain of influenza from swine was able to exchange RNA segments with a human strain which produced a strain of the swine flu that was able to infect humans. See figure 2.

Genetic recombination within viruses is relatively rare but is still possible. Recombination in influenza A viruses can occur in two different ways: non-homologous recombination and homologous recombination. While non-homologous recombination has occurred within the influenza A virus before, homologous recombination within the influenza A virus is incredibly rare.4

Non-homologous recombination in influenza A occurs between two different RNA segments and introduces new genes into the viral genome. Homologous recombination in influenza A is believed to result from template switching during transcription of viral RNA which is extremely rare.

The process of genetic recombination is beyond the scope of this article and your course; however, it is helpful to know that recombination can be used by the influenza A virus to evolve.

Since influenza first affected humans in 1918, re-assortment of human influenza and bird influenza has developed new subtypes. For example, in 2009, there was an outbreak of H1NI in humans. Typically, bird influenza subtypes do not infect humans however, pigs act as a viral mixer since both human and bird influenza subtypes are able to infect pigs.4 As a result, of pig infection, influenza re-assortment caused a new generation of influenza viruses to be created that can infect both humans and birds.

Marburg and Ebola are filoviruses that cause significant hemorrhage, organ failure, and death if left untreated.4 In 2013, there was a large outbreak of Ebola in West Africa that cause widespread illness and death within that region. Molecular analysis of Ebola and Marburg viruses can give us insight into its origin and evolution. Ebola was first discovered in 1976 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and scientists do not know where it comes from.5 Research suggests that Ebola is animal borne with bats or non-human primates being suspected sources. Non-human primates act as the viral reservoir and can transmit the virus to other animals including humans.4

Unlike the airborne influenza A virus, Ebola is transmitted through direct contact with the bodily fluids such as blood, semen, and phlegm of an infected animal that is living or deceased.5 Like Ebola, the Marburg virus is transmitted via infected bodily fluids. Marburg virus was first discovered in 1967 when laboratory workers in Germany and Yugoslavia were infected via contact with African green monkeys from Uganda.4 Like Ebola, the Marburg virus most likely originated in non-human primates.

Just like the influenza A virus, Ebola and Marburg viruses evolve by mutations, re-assortment, and recombination; however, these viruses evolve at a much slower rate compared to influenza A viruses.

Viruses evolve using three different methods: mutations, re-assortment, and recombination.

Viruses promote genetic diversity in the host organisms they infect. When a host is infected with a virus, their bodies modify their genome to better prepare the organism to fight the virus during a second infection.

It is estimated that the first viruses evolved 3.5 billion years before humans evolved.

Vaccines that reduce the replication and transmission of viruses do not speed up viral evolution as these types of vaccines reduce the chance of viral mutations.

RNA viruses such as influenza and SARS-COV-2 mutate the fastest.

Flashcards in Evolution of Viruses32

Start learningWhat theory of viral origin suggests that viruses originated from a complex free-living ancestor that devolved over time by losing genetic material?

Regressive Theory

This term refers to an acellular, parasitic piece of genetic material that is not classified within any kingdom.

Virus

Viruses are all identical and have the same genetic code.

False

Viruses that store their genetic information as RNA are called dsDNA viruses.

False

What is a retrovirus?

A virus that stores its genetic material as RNA.

What is a negative sense RNA virus?

A virus that has genetic code that is complimentary to the viral mRNA.

Already have an account? Log in

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in