StudySmarter - The all-in-one study app.

4.8 • +11k Ratings

More than 3 Million Downloads

Free

Americas

Europe

Individuals within a species exhibit a wide range of phenotypic characteristics. This variation is important as it ensures the survival of a species in changing conditions; members within a species that harbour favourable characteristics are more likely to survive and reproduce.

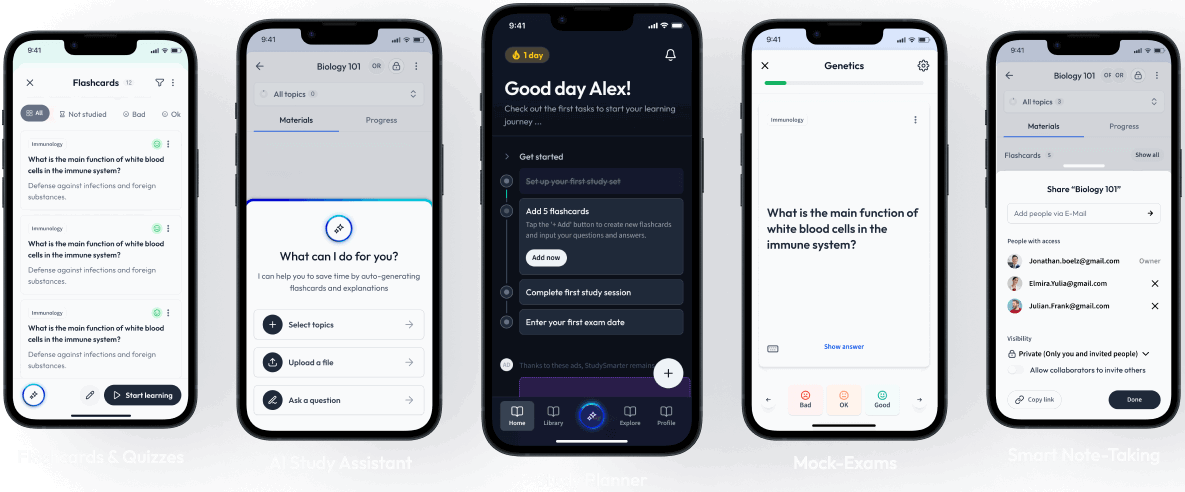

Explore our app and discover over 50 million learning materials for free.

Lerne mit deinen Freunden und bleibe auf dem richtigen Kurs mit deinen persönlichen Lernstatistiken

Jetzt kostenlos anmeldenIndividuals within a species exhibit a wide range of phenotypic characteristics. This variation is important as it ensures the survival of a species in changing conditions; members within a species that harbour favourable characteristics are more likely to survive and reproduce.

The phenotype refers to observable traits or characteristics in an organism, such as eye colour and fur colour. Not all phenotypes are visible, such as blood type.

Genetic factors, environmental factors, or a combination of both cause phenotypic variation, which describes the variation found within a species or between species. For example, humans display vast phenotypic variation, including skin colour and eye colour.

Phenotypic variation describes the variability in phenotypes within or between species.

While members of the same species share the same genes, genetic differences occur when different individuals harbour different alleles. In real-world populations, the frequencies of certain alleles might also change from generation to generation. In sexually reproducing organisms containing diploid cells, genetic variation arises from processes such as mutations, crossing over, independent assortment, and random fertilisation.

Diploid cells contain paired chromosomes, one derived from each parent. In humans, diploid cells have 23 pairs of chromosomes.

Mutations describe changes in the DNA base sequence that results in the generation of one or more new alleles. These new alleles may be beneficial, harmful, or neutral to the individual’s phenotype. Depending on the organism, mutations can occur fairly frequently. However, they are not always expressed. Even when they are, they may have little to no effect on the phenotype.

Alleles describe different versions of the same gene that arise from mutations.

Mutations occur throughout our lives and can happen in any kind of cell. Most mutations are harmless, but some can be harmful, and some are even associated with the symptoms of aging. However, not all mutations are passed on between generations. Mutations must happen in the germline – that is, the cells that form our gametes– to be passed on to offspring. Offspring don’t inherit autosomal mutations.

Autosomal mutations refer to mutations that occur in the non-sex chromosomes.

Diploid organisms undergo the process of meiosis to generate haploid gametes. During meiosis, crossing over occurs during which non-sister chromatids exchange alleles. In meiosis I, homologous chromosomes pair up very closely to one another. Due to the proximity, non-sister chromatids can cross over and get entangled together at crossing points called chiasmata. This entanglement creates enough stress on the DNA molecule to cause it to break and rejoin with the chromatid from the other chromosome, effectively swapping out a chunk of DNA. This swapping can result in a new combination of alleles on the two chromosomes. It usually happens at least once in each bivalent pair and is more likely to occur further away from the centromere.

Crossing over: the exchange of genetic material during sexual reproduction between two homologous chromosomes.

Independent assortment is the random alignment of chromosomes during metaphase which results in different combinations of alleles in each gamete.

During metaphase, chromosome pairs are pulled towards the equator of the mitotic spindle. Each pair can be randomly arranged with either chromosome on top. This orientation is completely independent of the actions of any other pair. The homologous chromosomes are then separated and pulled to different poles, leading to different combinations of alleles in each gamete. To determine how many chromosome combinations can result due to independent assortment, we use the formula 2n, where n is the number of chromosomes in a haploid cell.

For humans, this is 8,324,608 different combinations! This contributes hugely to genetic variation within a population.

The process of meiosis creates genetic variation between gametes, which means that gametes will each carry various alleles. Fertilisation occurs when male and female gametes fuse to create a new individual. In humans, the gametes are sperm and egg cells. Any sperm cell can fuse with any egg cell and share its genetic information, thus creating genetic variation.

The random fertilisation of gametes explains why heterozygous or fraternal twins do not look more alike than normal siblings. Heterozygous twins are formed when two eggs mature simultaneously and are fertilised by two separate sperm cells. Due to random fertilisation and the incredible genetic variety between the gametes themselves, there is almost no chance that two successive fertilisations will lead to the same combination of alleles. Homozygous or identical twins, on the other hand, are formed from the same egg and sperm, and therefore have identical genetic material.

The environment itself has relatively little impact on genetic variation. However, it can significantly influence organisms and change the way certain genes are expressed. While the genes can serve as a blueprint for an organism’s phenotypic limits, the environment determines where exactly within those bounds the organism lies.

While a plant may have all the genes necessary to grow tall and strong, if it is raised in an environment that does not have enough sunlight and resources, it will not grow to its maximum potential. In other words, the genotype dictates a phenotype, but the environment restricts it.

There are many examples of environmental influences that can lead to phenotypic variation in a population such as:

Variation in phenotype due to environmental factors does not usually cause genetic variation, and because of this, it cannot be passed on to offspring. For instance, something like the presence or absence of nitrogen in an environment does not cause an individual to mutate a new allele that allows it to survive better in those conditions.

Often, quantitative characteristics of organisms (such as height and mass) form a continuum rather than discrete phenotypes. These traits are often not controlled by a single gene. Instead, they are controlled by polygenes (many genes.) Environmental factors are important in determining where on the continuum an organism lies. While genetics might predispose individuals towards taller heights, factors like diet might restrict them to more average heights. If we were to measure the heights of a large number of individuals, we would obtain a bell-shaped curve known as the normal distribution curve. An important characteristic of this curve is that its mean, median, and mode are all equal, and all points along the curve are equally distributed around the mean.

Discrete phenotypes that are controlled by only one gene or set of genes, such as blood type or certain types of colouration, cannot be appropriately represented by a bell curve. In cases such as this, it is more appropriate to use bar charts to visualise trends in data.

Discrete data: data made up of whole numbers, e.g. shoe size.

Continuous data: data that may take any values, e.g. height.

There are two sources of variation in population: genetic and environmental.

While members of a population share the same genes, genetic differences occur when different individuals have different alleles.

A mutation is a change in the DNA base sequence that results in the generation of one or more new alleles. Mutations are the main source of genetic variation.

Variation may occur due to mutations, crossing over, independent assortment, or random fertilisation.

The environment itself has relatively little impact on genetic variation, but it can change the way certain genes are expressed. These changes are usually not passed on to offspring.

A normal distribution curve can depict continuous variation in a population.

Variation refers to the differences in the traits expressed by members of a population.

There are two sources of variation: genetic and environmental.

Homozygous or identical twins are formed from the same egg and sperm, and therefore have identical genetic material. However, some twins are heterozygous or fraternal. They are formed when two eggs mature at the same time and are fertilised by two separate sperm cells. There is almost no chance that two successive fertilisations will lead to the same combination of alleles; thus, heterozygous or fraternal twins do not look more alike than normal siblings.

Differences in eye colour.

It ensures the survival of a species in changing conditions.

Genetic and environmental

The variability in phenotypes that exists in a population.

It is observable in the phenotypes of individuals.

Flashcards in Variation Biology29

Start learningWhat are the two sources of variation in a population?

Genetic and environmental.

What is the primary source of variation?

Mutations.

What are the three sources of genetic variation?

Mutations, crossing over, and independent assortment.

Crossing-over occurs when ______ chromatids exchange alleles during meiosis.

non-sister

The presence of an allele on one gamete will not affect its chances of fusion with any other allele.

True

What is the formula for the number of possible chromosome combinations due to independent assortment?

2n, where n is the number of chromosomes in a haploid cell.

Already have an account? Log in

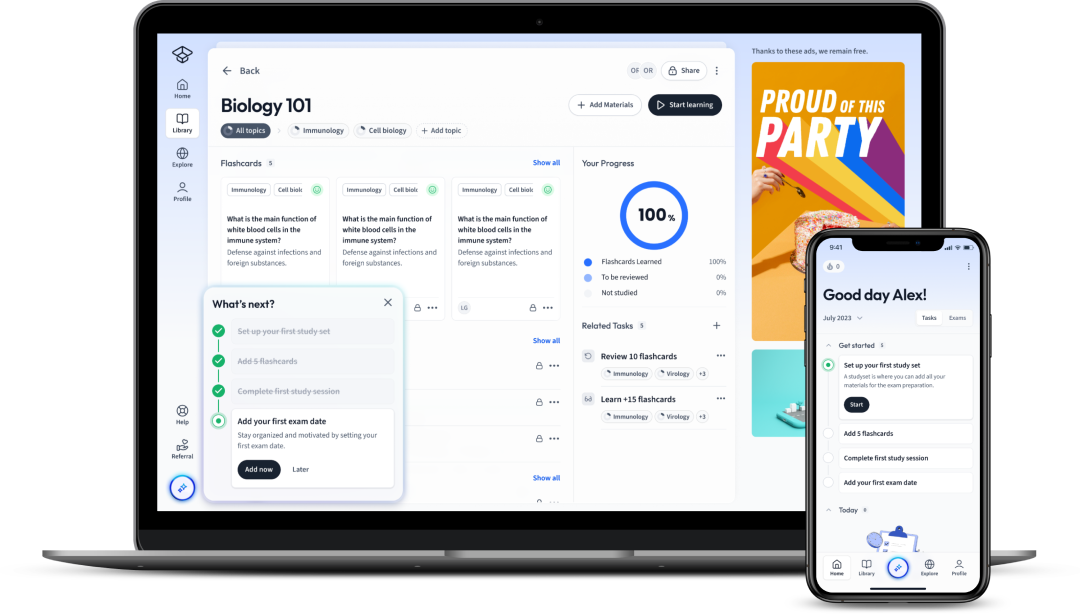

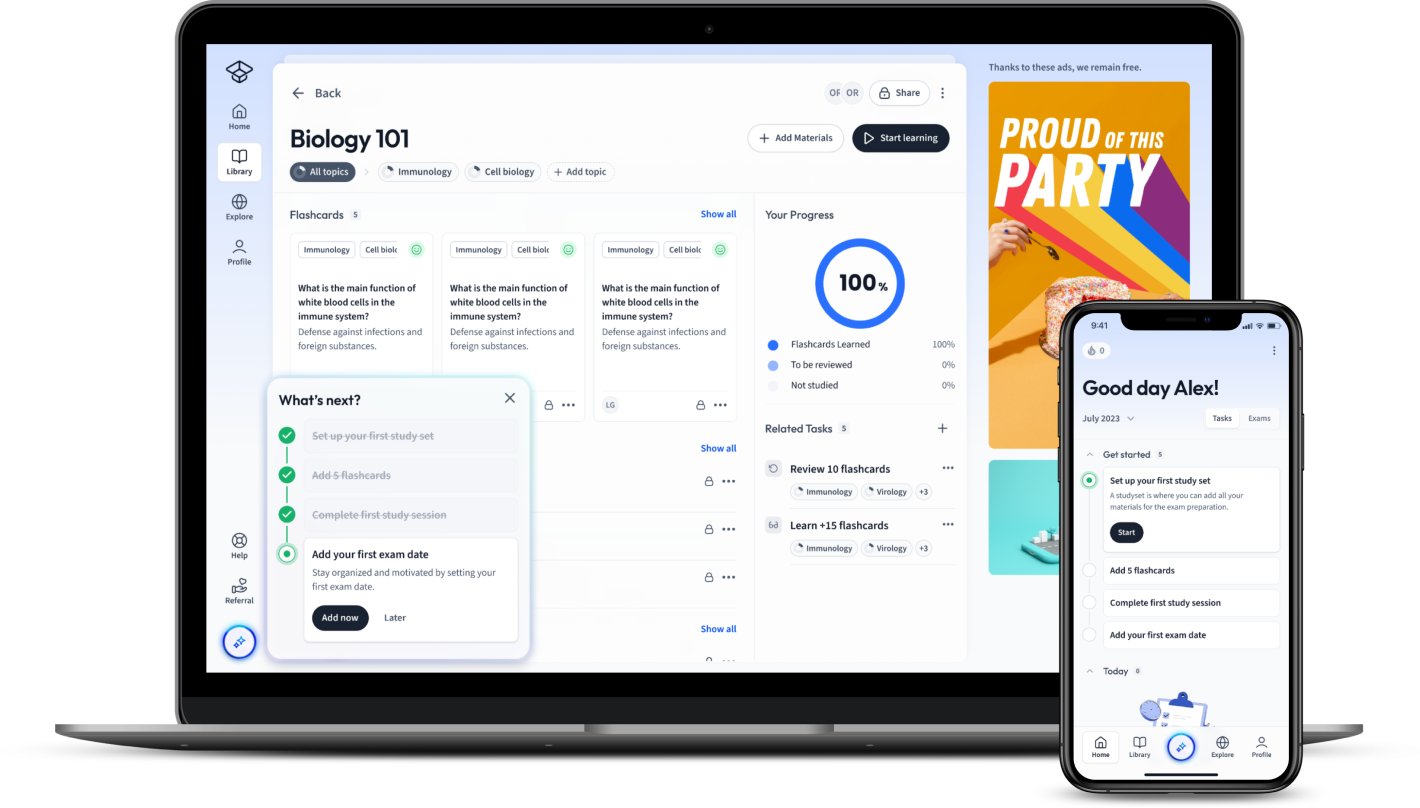

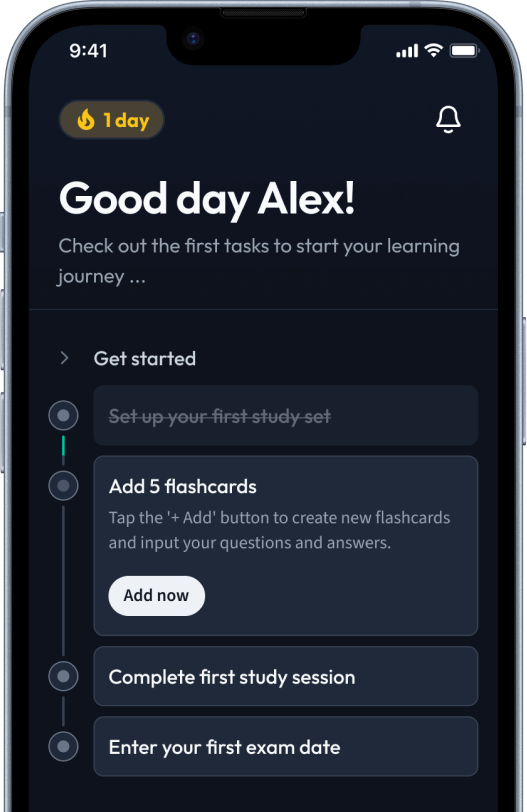

Open in AppThe first learning app that truly has everything you need to ace your exams in one place

Sign up to highlight and take notes. It’s 100% free.

Save explanations to your personalised space and access them anytime, anywhere!

Sign up with Email Sign up with AppleBy signing up, you agree to the Terms and Conditions and the Privacy Policy of StudySmarter.

Already have an account? Log in